Saint Luke’s in Hastings, Minnesota had come to a crossroads. A major project to improve access to the building for the disabled had taken a significant share of the endowment—and caused a rift in the congregation. Many chose to leave. Dollars left with them. Quickly, the reality became apparent to the congregation’s leaders: they could no longer afford a full-time rector. Difficult conversations followed. The rector, who had been among the first to see the writing on the wall, was—happily for the congregation—able to accept a change in her status in order to stabilize the parish’s finances. But a short-term fix could not be a long-term solution. Made aware of the parish’s circumstances, the head of the judicatory—in this case, the bishop of the Episcopal Church in Minnesota—became involved.

James Jelinek, then the Bishop of Minnesota, had seen stories like Saint Luke’s before, and those experiences shaped his response to their circumstances. After visiting the parish and meeting with its leaders, he gave the community two options. They could decide to prepare the affairs of the parish for an orderly closure. Said differently, they could give up. Or they could reimagine how church was done. They would start by undertaking a survey of the entire membership of the parish, asking each member to identify their gifts for contributing to the ministry of the parish—their talents, their gifts, their skills, and yes, their financial ability to contribute. They would compile the findings of that survey and decide if the resources existed for them to carry on. If they chose that path, they would identify a team of leaders from among themselves—all lay people—to share the necessary work of a faith community: the administration, the property, the Christian education, the pastoral outreach, the mission and service to the world outside the church. And oh, yes, the worship. Two of the members of that leadership team, the bishop explained, would be held up by the whole community as the right people to provide sacramental ministry. And they would be ordained by the bishop. Then, while doing their work in the world and serving the church as ordained ministers, they would also be required to take part in a series of courses at the diocese’s School of Formation.

It was a tall order. Some members of the parish didn’t think they could do it. Others were perplexed at the idea of ordaining someone they might know. Someone sitting right next to them in the pews. Sure, there were natural leaders in the congregation—there are in every congregation. But ordain them?

In the end, that is what the parish chose to do. When I visited them, they had been living into their new model of ministry for nearly ten years. The two members of the ministry team who had been ordained—one a contractor, the other a civil engineer—had served alongside the previous rector during a two-year transition period; after that, they had been on their own in providing for the ordained needs of the community. As I met with them after church one Sunday, I was introduced to members of the new ministry team, members of the parish who had just begun to step into their duties as the successor generation of that first group of ministry leaders. Two of them, through a process of discernment, had been identified as the next ordained leaders of the community and had already begun to prepare for their ordinations.

• • •

Congregations are as different as the people in them, and certainly as different as the people who lead them. Those differences are in part a function of size, as Arlin Rothauge noted in his now-classic pamphlet Sizing Up a Congregation For New Member Ministry.[1] Rothauge’s insight was that congregational size tends to shape the style of communication and collaboration within faith communities—and, in consequence, the role of, and expectations focused on, the senior pastor in these communities.

Anyone who has experienced more than one church along their journey can testify that each faith community—just like each workplace, or each neighborhood, or each school—has a unique personality. We often say that different groups have a different “feel” to them. What we mean is that the community, as a group of people gathered for a purpose, have an agreed (if not always explicit) sense of what matters and what does not, how things are done and why they are done that way, and what sort of contributions to the community’s work and witness are most welcome—and which are not.

The personalities of congregations are varied, despite the fact that virtually every congregation would describe itself, first and foremost, as “welcoming.” What we usually mean by that word, even if we don’t realize it, is something more like, “We’re really welcoming to folks who can figure out pretty quickly how we work and what we care about, and who find themselves comfortable in that kind of place.” While every congregation should strive to be as welcoming as possible, congregations are made up of humans—and humans have limits, one of which is a tendency to gather into groups of people who quickly realize, and find assurance in, their similarities. Not every congregation is for everyone. Sometimes what makes for the fit, or lack of it, is the way in which the community understands, shapes, and responds to the role of its ordained minister.

Of course, congregations were not created by God to always and forever be at a specific size. Congregations grow and shrink, as do the neighborhoods around them, the ministries to which they are called, and the resources at their disposal. The identity of a parish, its ethos and ways of doing things, can be deeply shaped by years of ministry at one general size and shape—and then find itself challenged when a change in circumstances makes a transition inevitable.

Alice Mann, in her book Raising the Roof: The Pastoral to Program-Sized Transition, focused her research on the second and third of Rothauge’s categories of congregational size. She looked in particular at the idea that congregations were striving to grow larger, and were encountering difficulties in shifting from the structure and communication patterns of one size to those more appropriate to the other.[2] But congregations don’t always change by growing larger. Sometimes they “grow smaller,” a seemingly nonsensical but increasingly meaningful idea. It is true that the difficulties facing some faith communities are overwhelming, and that sometimes the inevitability of closure can only be staved off by selling off the family silver (or spending down the parish endowment). But it is not true that all congregations that become smaller are destined for trouble. Some of them become stronger, deeper, more centered on the message of the gospel, and more intentional in their ministry to the world beyond the church as they contend with shifts in demographics and dollars. Getting to that outcome is not (or not merely) a matter of God’s grace; it is a task for leadership, and the result of both prayer and planning.

In short, some congregations are better positioned to “grow smaller” than others. In my research visits to a number of congregations, I found a wide variety of models of ministry, but a fairly consistent set of themes about what separates those able to adapt from those that cannot. Of course, not all congregations successfully responding to changes in their circumstances adopt a bivocational approach to ministry; there are other ways of structuring ministry, and other possibilities for moving toward a future very different from our past. In what follows, I’ll focus on what I observed to be consistent among congregations that have not only shifted into a bivocational approach to ministry, but that have found in it a source of growth and renewal.

The Place of the Pastor

Just as there are many different kinds of congregations—in terms of size, demography, spiritual gifts, and “community personality”—so there is considerable variety in the role of the pastor within the congregation. And, just as, in chapter 1, we explored the needs of individual pastors in expressing their gifts for ministry in an ordained role, it’s equally true that the congregation has needs—and expectations—about what its role will be in the relationship between pastor and parish.

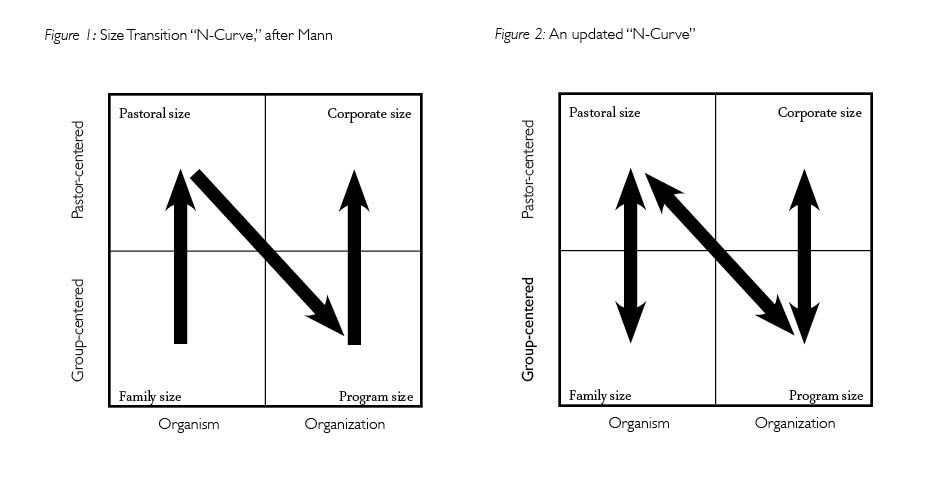

In Raising the Roof, Mann offers an interesting broad-brush insight into the relationship between the size of a congregation and the relative emphasis that congregation is likely to place on the person and the gifts of the pastor—or, alternatively, on the gifts of those within the laity. She describes an “N-curve” (figure 1) that shows an expected direction of growth, and with it a key aspect of changes in expectations, roles, and patterns of collaboration in the ministry of a community. But growth in the church never happens in one direction—and certainly is not happening that way today. As congregations “grow smaller” (something very different from “shrinking”), Mann’s N-Curve takes on something of a different shape—which we can represent with the slightly modified form of her original idea, shown in figure 2.

What Mann’s insight reveals is that the role of the pastor is different in different types of congregations, and, therefore, so are the skills and gifts across the whole congregation on which flourishing depends. Taking this line of thinking one step further, the suggestion of Mann’s analysis is that congregations that are relatively more “group centered” than “pastor centered” will likely find themselves better suited to a bivocational pastorate, exactly because the ethos of such congregations already places a high degree of autonomy on, and depends for much of its energy on, the initiative of its lay members.

Going on just the examples of the parishes I visited in researching this book—admittedly a limited sample—that hypothesis is borne out in experience. And there is an irony here, one important to consider at some length.

You might think that there is a simple, linear relationship between congregational size and the need for, and openness to, a bivocational pastorate. The idea would go something like this: the bigger the congregation, the less disposed and the less suited it will be to a bivocational structure for its ministry; the smaller the congregation, the more open and prepared it will be for experimenting with such a structure. That intuitive judgment seems to fit well with the needs of parishes, because the bigger the church, the less apparent need there is for changing the basic structure of how ministry is done.

But that turns out not to be the case. The ability of a congregation to adapt to a bivocational model of ministry and to grow along with it is not necessarily determined by its size. Instead, it has much more to do with the way that relationships and expectations have been expressed in that congregation—whether it has been “group centered” (family sized or program sized) or “pastor centered” (pastoral sized or corporate sized).

Group-centered congregations turn out, perhaps not surprisingly, to be the congregations most likely to find that a bivocational ministry offers new paths for growth and vitality. They have a community ethos of openness, affirmation, and engagement toward the gifts and energies of individuals and groups within the community, and, most critically, do not chiefly derive their identity from the person of the pastor.[3] We’ll explore this in a little more depth in a later section.

This observation opens a few interesting and counterintuitive paths toward the future—at least for some congregations. To stick with Rothauge’s categories for a moment, if group-centered congregations are most likely to succeed in adapting to a bivocational ethos of ministry, then two kinds of congergations—very small, family-sized faith communities (the “less-than-fifty-active-member” churches), and rather larger, 150- to 350-active-member program-sized churches—are likely to be the best candidates for making a successful transition to this approach. It’s worth restating here a point made earlier, and one that will come up again: A bivocational ministry is a work of the entire congregation; it is not merely a way of describing the working life of one person who happens to be ordained. It’s a ministry in which an ordained minister (1) lives out the life of ministry with jobs both in the church and in the secular world, (2) models a way of living into the ministry of the baptized both inside and outside the church in a way that helps all members of the community to do the same, in ways appropriate to their circumstances, and (3) shares both the responsibility and the authority of aspects of the shared ministry of the community with lay members of the community. It turns out that the right place from which to do these things need not be, and ideally will not be, in the very center of the social structure of the congregation, the typical focal point at which the pastor is situated.

It may seem odd to place pastors of larger parishes in the category of those who might succeed in a bivocational pastorate. Don’t the pastors of large congregations have quite enough on their plate just attending to the demands of parish ministry? A moment’s reflection on the question suggests a different picture. In larger congregations, the resources often exist for two or three ordained ministers to be on the staff. In these settings, the senior pastor often is deeply engaged in community leadership in ways outside the life of the church—serving on boards, starting non-profits doing work aligned with the ministry goals of the parish, or perhaps teaching in a local setting of higher education. Exactly because these parishes are so well-resourced, part of the ministry exercised by the ordained leadership can be outside the church in ways that, very similar to pastors in poorly-resourced churches, help to make their perspectives on the life of discipleship more relevant to the experience of people in the pews.

So it is by no means only small, economically precarious churches that might find the bivocational model of ministry both attractive and a source of spiritual growth. In fact, success in a congregation’s embracing and flourishing in a bivocational pastorate is not really—or at least not primarily—a matter of resources. Instead, what seems to be the critical element on which bivocational models of ministry is built is the presence of a group-centered ethos in the congregation. What does that look like in practice?

Moving Places

When I first came as the ordained leader to Saint John’s in Newtonville, the parish had searched for a new full-time rector only just a few months before. They had issued a call in great hope to someone who, before ever appearing on the scene, made it clear to the parish and the bishop that he was not yet ready to handle responsibly the pastoral confidences that come with being the senior pastor of a congregation. The parish had found itself in the painful position of withdrawing its call, knowing that the fundamental bond of trust upon which all successful ministry is built could not be restored.

Blessings sometimes come disguised as disasters. What the parish realized, as they sat with the pieces of a broken search process all around them, was that the longstanding tradition of that parish to have a full-time, fully benefited senior pastor had driven them to look for someone who would simply repeat the pattern, without really considering an alternative. But the disappointing end of the search brought a new clarity in considering the financial realities of the parish. There was no way to afford that model of ministry anymore, given the costs of that one full-time professional and the other costs associated with maintaining a small non-profit organization with its own building and grounds in eastern Massachusetts.

Describing new ways of sharing the work of that ministry between a new pastor (who turned out to be me) and the members of the congregation turned out to be the easy part. We drafted a contract, had it reviewed by the usual authorities in our judicatory, and went to work. The harder part was changing the culture, one that had grown up around the expectation of a full-time pastor: a person who was pretty much always available, who decided on everything from the hymns on Sunday and the themes in sermons to the kind of paper purchased for the office, and who represented the church in its dealings with everyone from the trash haulers to the landscapers.

Two simple questions turned out to be the most powerful tools available to us in helping us understand how that old culture worked and how we might change it. The questions were “What do you expect the pastor to do?” and “How necessary is it for a pastor to do that?”

At first we tried this simply as an exercise of posing these two questions in the abstract. But as time went on, we walked ourselves through a variety of imagined scenarios. What if someone comes through the door asking for a handout? What if the child of someone who was married in the church sixty years ago appears on the doorstep asking whether we can host a funeral for a parent who has just died? What if the alarm system goes off in the middle of the day when the nursery school is in session downstairs?

Asking questions like this, and dozens more like them, became a low-risk but powerful means of bringing to the surface a whole set of expectations that old culture had inculcated in us about what pastors should be and what they should do. And asking them in ways safely separated—at least initially—from actual cases in our lives together helped us find ways to question those assumptions, discern anew what was central to the call to ordained ministry, and reimagine how other necessary aspects of the community’s work might be done. Rather than a moment of crisis causing unexpected pain and misunderstanding as we adjusted to new ways of being a church together, we imagined those new ways as we thought through different scenarios. Eventually a picture of the more mutual sharing of responsibility and authority began to appear more clearly, and, as it did, people began to see new ways in which they could take up parts of the work of the community, because they found ways of becoming more deeply connected to their love of their community and the people in it.

The moment I knew Saint John’s had become a place with a different culture and a different spirit didn’t happen in a particularly celebratory way. It was four years after I’d begun my service as the pastor of the parish when, instead of being on a flight to return home after a business trip, I found myself flat on my back in a hospital bed a thousand miles from the church—on a Saturday. I’d presented myself to the emergency room not having the slightest idea why I had a seizing pain in my left flank. It turned out I had managed to assemble an impressive collection of kidney stones, that were building up a kidney infection behind them at a very fast rate. When I finally got my head around the fact that I wasn’t going to leave the hospital that day, I let the leaders of the parish know. I offered to do what I could to find a substitute.

“It’s okay,” came the answer. “Don’t worry. Just get better. We got this.”

And, wouldn’t you just know it, they really did. I learned the oddly liberating lesson that the whole life of the parish—even its worship life, that thing at the center of any faith community—didn’t depend entirely on me.

Life for the Pastor in a Group-Centered Congregation

What had happened in those four intervening years is that the culture of Saint John’s had shifted away from a long, deep history of being focused on the pastor toward something more about the community itself—centered, that is, on the people, rather than on the one person in a collar. I wish I could say this shift happened as the result of a clear strategy and a series of conscious, calculated steps. But it didn’t.

Instead, it happened because of the happy combination of a number of forces. It happened because the shift from a full-time to a part-time minister allowed the congregation to reassess its financial priorities and invest in things that had long been chronically underfunded. It happened because, in ways large and small, we all worked on asking ourselves what was really necessary about the ordained ministry within the community. Some things about that role were necessary, to be sure, but much less than we had all been raised to think. And it happened because people began to step into roles that they felt they could take on, or to try volunteer commitments they thought they might be able to handle—at first a few, and then more.

If you are a close reader of the works I’ve cited above, a thought may be occurring to you. Think back to a moment to figure 1. In describing the four sizes of congregation, Alice Mann also divides them into two groups: those that are more group-centered (family sized and program sized), and those that are more pastor-centered (pastoral sized and corporate sized). My point is that it is not a linear progression from pastor- to group-centered. The smallest sort of congregation (family sized) and the second-to-largest sort of congregation (program sized) are both group-centered types of congregations.

So you might be thinking—are you saying that a bivocational church is going to regress toward being a smaller, family-sized, group-centered congregation?

This much is certainly true: group-centered congregations tend to be better suited for life as bivocational congregations. The dynamic of a community in which groups cohere around ministries, tasks, and critical functions is much more easily aligned with the way a bivocational model of ministry has to work—with a genuine sharing of responsibility and authority among all members of the community, lay and ordained.

But here is something else to consider: All of the size-defined models of congregations familiar to many who have read books like Rothauge’s, Mann’s, and other observers of congregational life, are—in some fundamental sense—pastor-centered to begin with. They all presume the existence of the Standard Model of ministry—the pastor-as-full-time-professional, with all the rights and privileges (and costs) that go with that idea. This is not a critique so much as it is stating a fact. Rothauge was writing more than thirty years ago, and summarizing research conducted even earlier. Mann was writing just at the turn of the millennium, now nearly twenty years ago. While their insights are still important and helpful, the dramatic changes in church membership in the first two decades of this century, the rise of the “nones,” and the decline in intergenerational transfer of religious tradition and practice (that is, the percentage of children who take up and follow in either the religious practices of their parents or in one of their own choosing)[4] are changing in fundamental ways some of the economic assumptions on which our Standard Model was built.

In a way, all Christian faith communities are being pushed toward a more group-centered dynamic, if only because being a part of such a community is no longer something one just does because of social expectation or family tradition. As the church changes in response to broader social shifts, our faith communities will be increasingly characterized by people who are there by conscious choice—by an affirmative adherence to the basic claims of the Christian faith and a willingness to live in ways shaped by the expectations of discipleship. What this means is that churches will still be big and small and everything in between, but the people in them will be more likely to be purposeful in their membership and more naturally focused on taking up a part of the work of the community’s ministry. And that will mean a general shift toward more group-focused structures and attitudes across all churches—and a changing role, generally, for the ordained minister, one more narrowly focused on the gifts and tasks that truly and rightly distinguish the ordained ministry.

Most of the parishes I visited in the course of my explorations of bivocational ministry neither grew nor shrank once they shifted toward this model of ministry. They held their own—which in present circumstances has to be seen as a kind of growth by itself—and grew in ways not measured by numbers of people but by depth of commitment and engagement. Some of them were family sized; some of them were pastoral sized; only one of them was program sized. But all of them were, in important ways, group centered. All of them were communities in which initiative and authority were shared among all members. And all of them were places in which pastors had worked consciously to reinscribe their own understanding of the role of ordained leadership within Christian communities.

So What About Us?

You may be reading this book because your own congregation has reached a moment of decision about your future path as a faith community. You may be confronting the impossibility of affording a full-time pastor and wondering whether your community can adapt to the part-time presence of its ordained minister. There are many different forms of part-time pastorates. A bivocational model may prove to be a way for your community to flourish—but as you consider this possibility you should prayerfully consider a few things that seem to distinguish communities that succeed with this approach to ministry. They’re the qualities that seem to be more present than absent in congregations I’ve observed that have made a successful transition to a bivocational model, and have found ways to flourish within it.

Bench depth in the lay leaders of the parish

Bivocational congregations share the work of a community’s ministry between lay and ordained members in significant and substantial ways. Often—especially in small, pastor-centered parishes that function like pastoral-sized parishes even if they are actually smaller in number—lay leadership atrophies down to a core group of a dozen or fewer lay leaders who enter into a pattern of swapping necessary jobs and titles among them, unable to recruit other members of the community to take up their part of the work. This is, to say it candidly, a failure of leadership, if only because a key aspect of leadership is to see and affirm the potential contributions of all members of the community and to connect that potential to the work that needs doing.

By contrast, parishes that have relatively strong and capable members willing to make and keep commitments to take up part of the work may respond with eagerness to a new structure of ministry in which the ordained member(s) of the congregation has real limits on her (or their) availability and time. In my visits to bivocational communities, I found that the number of people involved, or willing to be involved, in roles of responsibility in the parish tended to be between half and two-thirds of the average Sunday attendance. That’s to say, in a parish like mine—which typically sees fifty people on Sunday morning—I could readily count between twenty-five and thirty-three people who could be recruited to take on some ministry of the parish, from the relatively substantial (serving as the treasurer) to the occasional (helping out at the twice-annual work days).

An ethos of problem-solving rather than problem-exploiting

Imagine the following scenario. It’s Sunday morning. You discover a leak in the ladies’ room sink off the parish hall. Water from the leak is dripping down into a classroom below, used by the nursery school that rents space from the church.

First possibility:

“Didn’t someone call the plumber about this?”

“I thought the administrator was going to do it.”

“Well, obviously she didn’t think it was very important, I guess.”

“The nursery school people are going to be bent out of shape about this.”

“I keep saying that the plumbing is just so old around here—it all should have been replaced.”

“I’m surprised the grounds committee hasn’t dealt with this already—they usually just do things without telling anyone else what they’re up to.”

Second possibility:

“Wow, we need to deal with this. I’ll call the plumber and leave a message on his machine—his number is in the contact book.”

“You know the nursery school folks better than I do—could you reach out to them?”

“Sure—I’ll do it later today, so they’re not surprised by this tomorrow.”

“I think Joe and I could probably get the water shut off to that sink and at least clean up the area that got damp downstairs.”

“That would be great. Thanks so much!”

Most of us who have spent much time at all in churches have experienced moments like both of these examples. Sometimes people show how much they care about something by critiquing the problem; sometimes they show it by imagining solutions. Both approaches can be helpful, but bivocational churches—at least successful and happy ones—tend to have an ethos focused on the second, rather than the first. The questions that spring to mind for just about everyone in the community are more along the lines of “How can I help?” or “What can we do?” rather than “What else can go wrong?” To say it in a single word, bivocational congregations have a strong sense of agency—a belief that they can act in response to challenges.

I have a favorite story about this from my own parish. One Sunday morning, with about ten minutes to go before the ten o’clock service and most of us scurrying around with our last-minute preparations, the telephone rang. Anyone who has ever answered a church telephone on Sunday morning knows that the chances are well above 90 percent that the caller on the other end is going to ask, “What time is the service this morning?”

I knew that the outgoing message on the telephone says, among other things, that we have services at eight and ten on Sundays. I also knew that if the phone was ringing and I didn’t pick it up, it would be noticed. So I ran over and picked up the phone—to get the predicted result.

The following week at the vestry meeting I shared that story with the lay leadership and concluded by asking, “Should I have answered the phone?”

The responses came from around the table:

“Of course not. That’s what the message machine is for.”

“But then again . . . what if someone had needed something?”

“What could anyone need at ten minutes to ten on Sunday morning?”

“Still, it seems weird to let the phone just ring with everyone here . . . .”

“But that’s a time that Mark shouldn’t have to be distracted by the telephone.”

No conclusions were reached, no motions were offered or votes taken. But the next Sunday morning, after the eight o’clock crowd had downed their coffee and cleared out, I walked into the office to find Charlie, a member of the vestry, sitting at the desk with his coffee and calmly reading the newspaper. He took in the surprise on my face, turned back to the paper, and simply explained, “I just thought the phone might ring.”

I love this little story for a lot of reasons. First, Charlie saw the need and put himself forward to address it. There was no need for a committee, a plan, a task force, or a mission statement. Moreover, because his solution to a clear problem was so eloquently simple, hearing about what he had done caused a small (and, on my part, prayed-for) epiphany to break forth: others began stepping forward in similar ways.

Yet even more important than all of this was the spirit that Charlie’s simple act embodied: It is better to act in a way aspiring to solve a problem than in a way tending to complicate it. That sort of spirit turns out to be synergistic for all sorts of good purposes, and it is well worth the effort required to inculcate it—by modeling it, by celebrating and affirming it when it happens, and by celebrating its accomplishments.

An appetite for experimentation—and a tolerance for failure

Changing fundamental assumptions about how ministry is structured is not an easy business. It touches the most important aspects of a community’s life together—not only requiring shifts in patterns of expectations between the pastor and the members of the community, but rethinking priorities in the budget, relationships with the principal actors outside the community (the city or town, the neighbors, the vendors, the tenants), and the ways in which decisions are approached, made, implemented, and assessed.

All of this requires trying a lot of new things. It requires clarity around what it means when something new “works,” and when it doesn’t.[5] And it requires a willingness to try things that might fail, to know when they’ve failed, and learn from those experiences. That seems straightforward—and to anyone who has ever been in a start-up company, it’s completely unsurprising.

But the church has very little experience with these values and ideas, at least in the last few centuries. The experience of the Protestant ascendancy in twentieth-century America accustomed us to the idea that what it meant to be a successful church was to be staid, firm, unchanging, and above embarrassment—things we could be (but should not have been) when we were culturally dominant. In those days, our idea of evangelism was, in essence, to put on our best clothes and stand with a smile at the door of the church on Sunday morning. With an inheritance like that, experimentation can feel like selling out important traditions and long-standing ways of making meaning. Even trying new things feels like a silent vote of no confidence in our own inheritance.

To see it that way is to take a very short-sighted view of the history of the church. There are no deep theological commitments involved in who represents the church to the nursery school downstairs or the vendors who pick up the garbage or clean the halls. There’s no deep sense of ordained ministry that needs to own those roles. We can imagine different ways of representing the church, different ways of organizing ourselves for the work we must do, even different ways of conducting the liturgy so as to emphasize the equal sharing of responsibility and authority between ordained and lay members. (We gave up the idea of the ordained minister walking up the aisle last in the procession, for example; I walk side-by-side with the Eucharistic minister of the day.)

We can experiment with very basic things—what we call ourselves, and how we describe ourselves to the community around us; how we describe our roles in the church; how we share work among ourselves. At one annual meeting, we imagined what we would call ourselves if for some reason Saint John were suddenly stricken from the roster of saints. It was an interesting exercise, and one that reminded us that the ancient practice of naming churches after saints as a way of appealing to the faithful is perhaps a little bit outmoded in a culture that has little if any grasp of the stories that made those saints so attractive as examples. Not surprisingly, many of the emergent churches have figured this out and acted accordingly; down the street from us is “Elevation Chapel,” and near where I work in Amherst, Massachusetts is “Mercy House.”

Trying new things means setting down what “success” will mean if an experiment succeeds, how long it might take to evaluate whether success has been achieved, and what resources from the community will be needed to give the experiment the best chances of working. A simple example is the question of starting a new worship service. What resources will it take? Time, yes; perhaps additional support from the parish administrator and the custodians; it may impose slightly increased utility costs. What will “success” look like? Will it be a minimum attendance, or growth in the overall average Sunday attendance? Will it be some additional, less quantifiable quality? At what point after the experiment begins will it be appropriate to take stock about what impact it has had on the community, both in terms of benefits and costs? A month? A season? A year?

A clear sense of the community’s spiritual charism

If each congregation has a distinct personality, then each congregation receives from God a unique set of spiritual gifts. Said differently, each faith community is blessed with its own distinct charism—a quality, or depth of skill, at certain aspects of ministry.

Most of us have an idea of what a church does that comes from an experience of relatively large churches. A church offers a beautiful service of worship with a range of music. It offers Christian formation for people at all life stages. It offers pastoral care to those who are ill or in life transitions. It provides outreach to those in need. It works to bring people who are outside the church or unaffiliated with any faith community into the embrace of the community. It witnesses to the claims of the gospel in the world.

Smaller churches often feel weighed down by a sense that they lack the resources to do all these things. Often, a result—sometimes amplified, consciously or otherwise, by the attitudes of the larger polity or denominational structure—is that they question the legitimacy of their ministry. My experiences with congregations succeeding in a bivocational structure of ministry nearly always included a story about focusing on the things the community did well, and being less concerned about being a full-service spiritual supermarket. Some parishes had a beautiful liturgical tradition, and became “destination churches” for the quality of that observance. Some had strong preaching traditions. Some have creative expressions of liturgy—a praise service, a Celtic worship service, a contemplative service. Others were more centered in outreach to those in need, and drew their identity, sense of purpose, and energy from that focus. Others had strong gifts for inclusion and welcome, becoming communities where acceptance becomes the rule by which other expressions of ministry are shaped.

The point is that when the structure of ministry in these communities shifted, either of necessity or choice, to a bivocational model, the work began with asking—and praying on—a fundamental question: What have we been gifted to do? What are we good at? A different way to ask this is—what do we find real joy in doing together? Whatever that strength is, in it lives a clue from the Giver of all gifts as to the purpose to which God is calling that community.

Financial stability

The good news is that a shift from the Standard Model to a bivocational model can have immediate, and generally positive, impact on the finances of a faith community. Think of it this way: In 2015, the Episcopal Church reported that the median total compensation for a full-time priest in the smallest-sized (family sized) parish was $59,847.[6] Allowing for modest inflation since then, let’s say that number is now $60,000. On top of that, imagine that the full-time cleric depends on the church for access to health insurance. Conservatively, the costs of that to the parish will be about 30 percent of the total salary, or an additional $18,000. And then—at least in the Episcopal Church—the parish will be required to contribute 18 percent of the cleric’s total compensation toward a pension plan; there’s another $10,800. Our “Standard Model” cleric now costs nearly $89,000—and that’s the lowest part of the range.

There is nothing wrong—let’s be clear—about a ministry that involves full-time professionals. But it is not clear that this should be the norm in all cases, much less the standard of what constitutes a church. So let’s construct a different example. If that same church were to decide on a bivocational model for ministry, they might hire an ordained person on a part-time basis. Let’s assume that this person has another job that provides them with access to health care benefits. That means they’ll likely have to work at least 70 percent of their time for that employer. They’ll have only 30 percent of their time to give to their work in ministry, and that 30 percent will be a pretty strong upward limit on the time they have available.

But it also means that the compensation for this person will now be more like $18,000. There won’t need to be a 30 percent addition for health insurance, although some additional payment to help pay for health care may be opted for. The pension contribution will still need to be provided for—here, $3,240. The total cost for ordained leadership in the community would thus be $21,240—or just about a quarter of what it was in the Standard Model.

This scale of change can help a parish stabilize its finances, but it cannot be the solution to a problem of chronic underfunding. If the parish is consistently drawing down capital from its endowment to balance the books at the end of the year—essentially, regarding those funds as a savings account, rather than a source of additional income—then a deeper problem is present, one unlikely to be addressed with a change in ministry models. If the income generated from active members of the parish—those giving through annual or consistent gifts—is not sufficient to cover the operational costs of the congregation, that can be a warning sign as well.

In the case of my own parish, the change in ministry models meant that the income from pledges provided more than we needed to pay for all members of the staff. (It also meant that the rector was no longer the highest-compensated member of the staff.) The building was made to pay for the costs of running the building (through rental income). The income from endowment was turned to other purposes in ministry, as well as catching up on deferred capital improvements to our century-old building. Our financial health has improved—and our numbers have grown, modestly, in the period since we implemented our model.

A set of needs outside the doors that the community strives to serve

Archbishop William Temple famously quipped, “The church is the only society that exists for the benefit of those who are not its members.” The truth of this statement is so deep that it may also be stated in the inverse: A society that does not exist for the benefit of those who are not its members may be many things, but it cannot be a church. To be a church means to have ways of identifying and serving the needs of those outside the doors. There is no limit to the ways in which this can be done. It can be through contributions of funds, of food to the local pantry, or of time to voluntary societies serving the needs of others. It can be through mission trips or through pastoral outreach to the homebound. It can be through the creation of sanctuary space or other forms of support for refugees. But there must be some form of outreach. A gathering of disciples is distinguished by its work to reach beyond its own membership to address the needs of the world beyond its own.

A shift to a bivocational model of ministry typically brings with it a reorganization of the financial commitments and priorities of a faith community. That brings as well a moment of opportunity for the community to identify, and focus renewed resources toward, an outreach beyond its own walls. It may well be that the need is just across the street, or down the block. Searching out and addressing such needs can give a smaller faith community a sense of real and substantial accomplishment, which in turn can help strengthen confidence and a sense of holy purpose. Or there may be a historic connection between the parish and a mission need more globally defined, one that might be bolstered with new resources, energy, and vision.

An awareness of its own understanding of leadership

At the close of the previous chapter we looked at how questions of identity intersect with the exercise of authority by an individual leader. The forces shaping our identity are both individual and social; some aspects of our identity are determined by our genetic inheritance, some we choose for ourselves, and some are imposed on us by cultural narratives and socially constructed expectations.

Communities, as well as individuals, have identities. A congregation may think of (and speak of) itself as a working-class congregation; a black church; an Anglo-Catholic parish; an urban, suburban, or rural congregation; a welcoming community; or any one of a number of other familiar phrases we use to describe ourselves, each one of which is layered with meaning.

Because leadership is inescapably a social phenomenon, how a given congregation responds to the particular demands of a bivocational pastorate—and to the skills and gifts of a particular bivocational pastor—will be shaped by aspects of that community’s identity. The history of leadership style matters. A congregation may have a long tradition of strong, top-down leadership; that will form part of its identity, set the terms of what it expects leaders to do, and create both opportunities and challenges for whomever steps in to offer a bivocational model of pastoral ministry. So, too, the history of how the community came to be matters; a congregation may be in an urban, historically working-class community, in which a certain group (or groups) has long had a strong presence in the congregation, groups that have their own culturally shaped understanding of how leadership looks and sounds.

It’s important to make clear that this is not an observation about “good” and “bad” forms of leadership. There are plenty of examples of both across all leadership styles, and all varieties of communities. All leadership in the church is subject the understanding that it serves a holy purpose: helping individual believers find and express in the fullest possible way their unique baptismal gifts, and building up from these individuals a gathered community of believers and fellow-ministers who work to proclaim, and live by, the call of the gospel. But this way of describing the purpose of leadership leaves open a wide latitude of possibility for the Holy Spirit in bringing together individual pastors, with their particular gifts, needs, identities, and ways of expressing leadership, with individual communities, which equally have their own blessed particularities as well.

Ultimately, leadership is both empowered and bound by the realities of the social context in which it is exercised. Congregations that are on the path of considering shifting toward a bivocational model of ministry do well to begin with thoughtful reflection on how leadership has been exercised throughout the history of the community, both by ordained and lay leaders. This really is an exercise of raising what are nearly always subconscious and unspoken realities to a conscious and explicit level: How does the community itself understand and respond to different styles of ministry? What are the ways in which the community perceives the intersections of personal identity with expected (and accepted) expressions of leadership style? A congregation that hopes to move in the direction of a bivocational expression of ministry, but has a longstanding history of being strongly pastor-centered in both its own identity and its decision-making patterns, may well have difficulty adjusting to the sharing of both responsibility and identity in ministry characteristic of bivocational parish life.

• • •

One last word of caution: These qualities are indicators of the sort of congregations that can successfully adapt to, and thrive as, bivocational communities. They’re not guarantees of an ability to do so. Transitions are always difficult, and can be fraught with risk, the potential for loss, and the prospect of disappointment.

But there are significant advantages to growing into a bivocational community. The growth of all members in the ministry of the community moves significantly from an interesting idea to a vivid reality. The gifts of and need for the ordained ministry become clearer as its purpose is focused and clarified. The resources of the community can be reimagined and reorganized. And the whole of the community takes a higher sense of ownership in the life and work of the church—which is, as it turns out, a key component of a church that is poised for growth.

[1] Arlin Rothauge, Sizing Up a Congregation for New Member Ministry (New York: Episcopal Church Center, 1983).

[2] Alice Mann, Raising the Roof: The Pastoral-to-Program Size Transition (Bethesda, Md.: Alban Institute / Rowman and Littlefield, 2001).

[3] In the previous chapter I mentioned in passing the curious practice of outdoor signs. Strange though it may seem, I found this single piece of hardware to be a fairly telling (if simple) indicator of whether a parish would easily adapt to a bivocational pastorate. In none of the parishes I visited that were thriving in this style of ministry was the pastor’s name (or the names of the ordained members of the ministry team) included on the outdoor sign—e.g., “The Rev. John Doe Smith, Rector.” This is a custom rarely seen on signs outside Roman Catholic or Orthodox churches; it seems to be a practice peculiar to churches in the Protestant family. But its presence does seem to telegraph the way in which the community gathered inside the building understands the place and role of the senior ordained member, and how it defines its identity with reference to that person.

[4] See, for example, Joel Thiessen and Sarah Wilkins-Laflamme, “Becoming a Religious None: Irreligious Socialization and Disaffiliation,” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 56:1 (May 2017), 64–82; DOI: 10.1111/jssr.12319

[5] On creating clear and effective ways of doing this important work, excellent guidance can be found in Sarah Birmingham Drummond, Holy Clarity: The Practice of Planning and Evaluation (Herndon, Va.: Alban Institute, 2009).

[6] Church Pension Group, “The 2015 Church Compensation Report,” 3; July 2016. https://www.cpg.org/linkservid/52804A0F-D7BE-3E5F-DFC951500B70F3C2/showMeta/0/